What is a deepfake? How to spot one before you fall for it

Hyper-realistic fake videos and images (“deepfakes”) are becoming harder to spot and easier to misuse. Nearly indistinguishable from the real thing, these AI-generated forgeries are used to deceive, scam, or manipulate unsuspecting victims. Learn how to recognise deepfakes and take the first step toward better online safety. Then, go one better and get an AI-powered security suite to help detect deepfakes and other advanced threats.

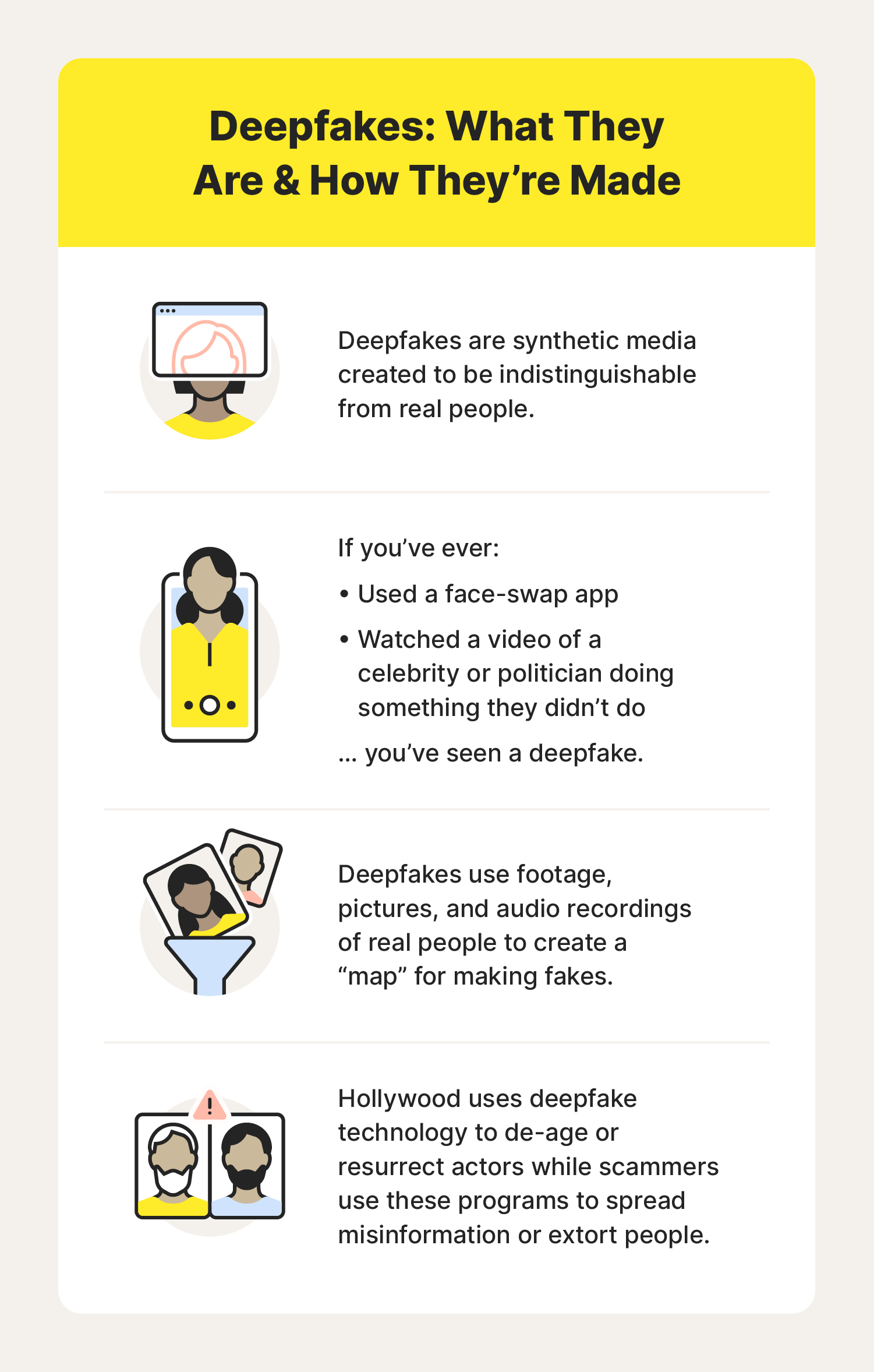

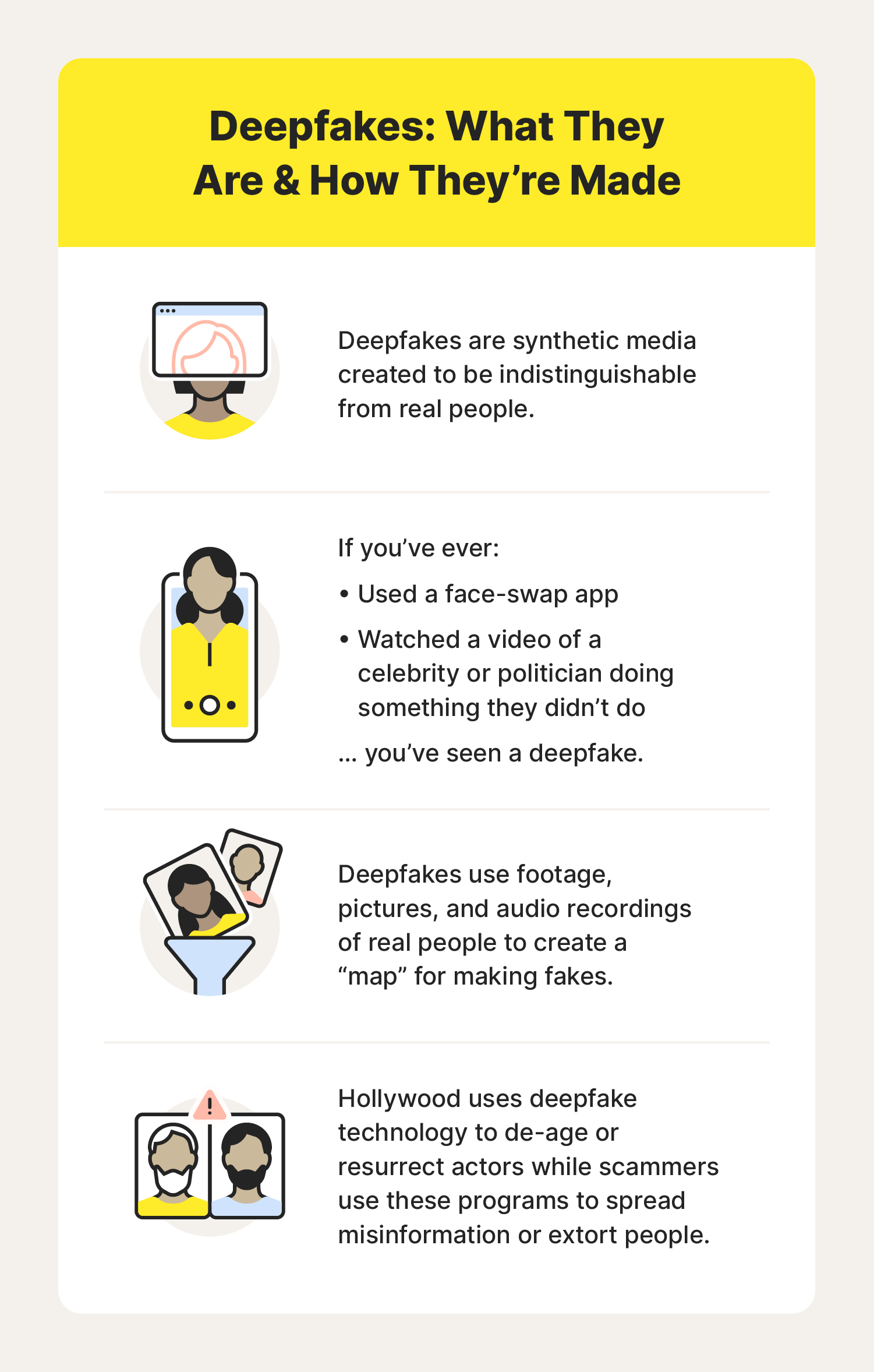

What is a deepfake?

A deepfake is an AI-generated video, image, or audio clip that convincingly imitates a real person’s face, expressions, or voice. Created using deep learning techniques, they often use swapped faces, synthesised speech, and altered footage. Deepfakes are created so seamlessly that they’re nearly identical to genuine content.

While the underlying technology was originally developed for entertainment and academic research, deepfakes and other AI tools are increasingly exploited for harmful purposes, such as AI-assisted scams, impersonation, misinformation campaigns, and even identity theft. As the technology becomes more advanced and accessible, deepfakes pose serious threats to personal privacy, public trust, and digital security. Recognising and defending against them is now a critical part of online safety.

How do deepfakes work?

Deepfakes combine existing images, video, or audio of a person in AI-powered deep learning software, which allows fraudsters to manipulate the information into fake pictures, videos, and audio recordings.

The software is fed images, video, and voice clips of people that are processed to “learn'' what makes a person unique (similar to training facial recognition software). Deepfake technology then applies that information to other clips (substituting one person for another) or as the basis of fully new clips.

What is needed to create a deepfake?

Deepfake technology is a combination of two algorithms — generators and discriminators. Generators take the initial data set to create (or generate) new images based on the data gathered from the initial set. Then, the discriminator evaluates the content for realism and feeds its findings back into the generator for further refinement.

The combination of these algorithms is called Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). They learn from one another by refining inputs and outputs so that the discriminator can’t tell the difference between a real image, sound clip, or video and one created by a generator.

To create a deepfake, the specialised software needs lots of video, audio, and photographs. The sample size of this data is important because it directly correlates to how good or bad a deepfake is. If the deepfake software only has a few images or clips to work from, it won’t be able to create a convincing image. A larger cache of visuals and sounds can help the software create a more realistic deepfake.

When deepfake AI technology first emerged, creating realistic photos or videos required expensive software, powerful hardware, and advanced technical skills. But that barrier has dropped. Today, deepfake tools are widely accessible — some even free — and can run on consumer-grade devices or through cloud-based platforms.

Who makes deepfakes?

Movie companies use the technology to:

- De-age actors (Harrison Ford in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny).

- Narrate films after actors have passed away (Anthony Bourdain’s voiceover in Roadrunner).

- Resurrect dead actors for parts in new movies by combining the performance of a living actor with digital recreations of the original actors (Peter Cushing in Star Wars: Rogue One or Paul Walker in Fast & Furious 7).

There are also amateur visual effects artists doing the same kind of work in an unofficial capacity.

Other companies (face-swapping apps, for example) make deepfake apps for individuals by placing their likenesses on famous actors in scenes from movies and television. The technology used for these apps is less advanced than what Hollywood uses, but it’s still pretty astonishing.

Educators are working to create new teaching materials that allow historical figures to speak directly to students to deepen connections between the past and present. Other groups are using this technology to bring people’s loved ones back to life through video missives and images.

But not all uses of deepfake technology are harmless. Criminals and bad actors are increasingly exploiting deepfakes for purposes that range from unethical to outright illegal. With the ability to make public figures appear to say or do anything, deepfakes can be weaponised to spread disinformation, interfere with elections, manipulate public opinion, and undermine trust in institutions.

What are deepfakes used for?

The entertainment industry makes deepfakes for movies and television shows, app companies offer face-swapping of images and video clips, individuals and organisations with political motives create them to spread fake news, and even criminals use the technology for fraud and blackmail.

An emerging cybercrime trend uses fake videos of celebrities to promote fake products. Exploitative people can make fake pornography, revenge pornography, and sextortion videos that violate people’s privacy while earning money by selling the material or threatening to release these videos unless a “ransom” is paid.

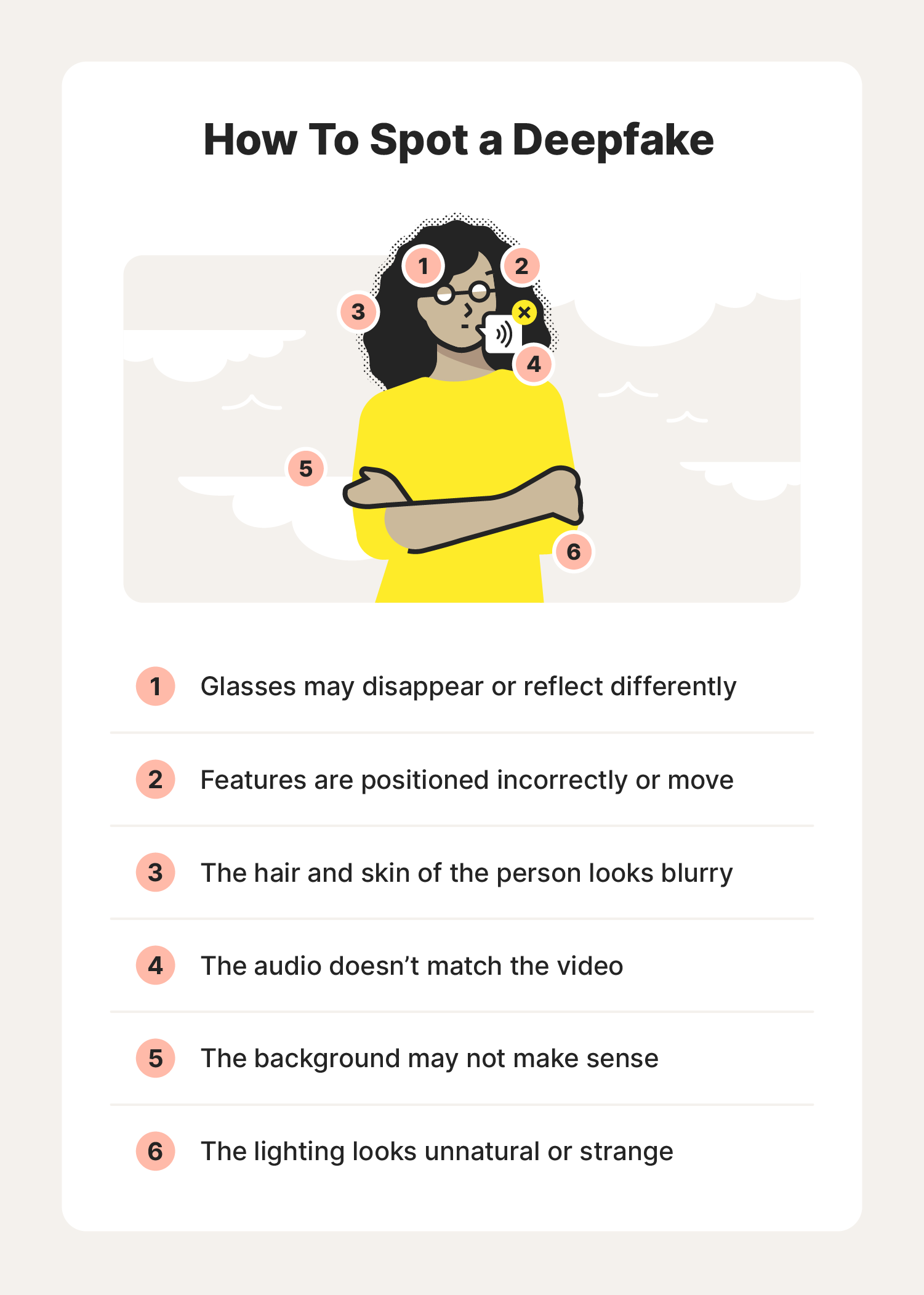

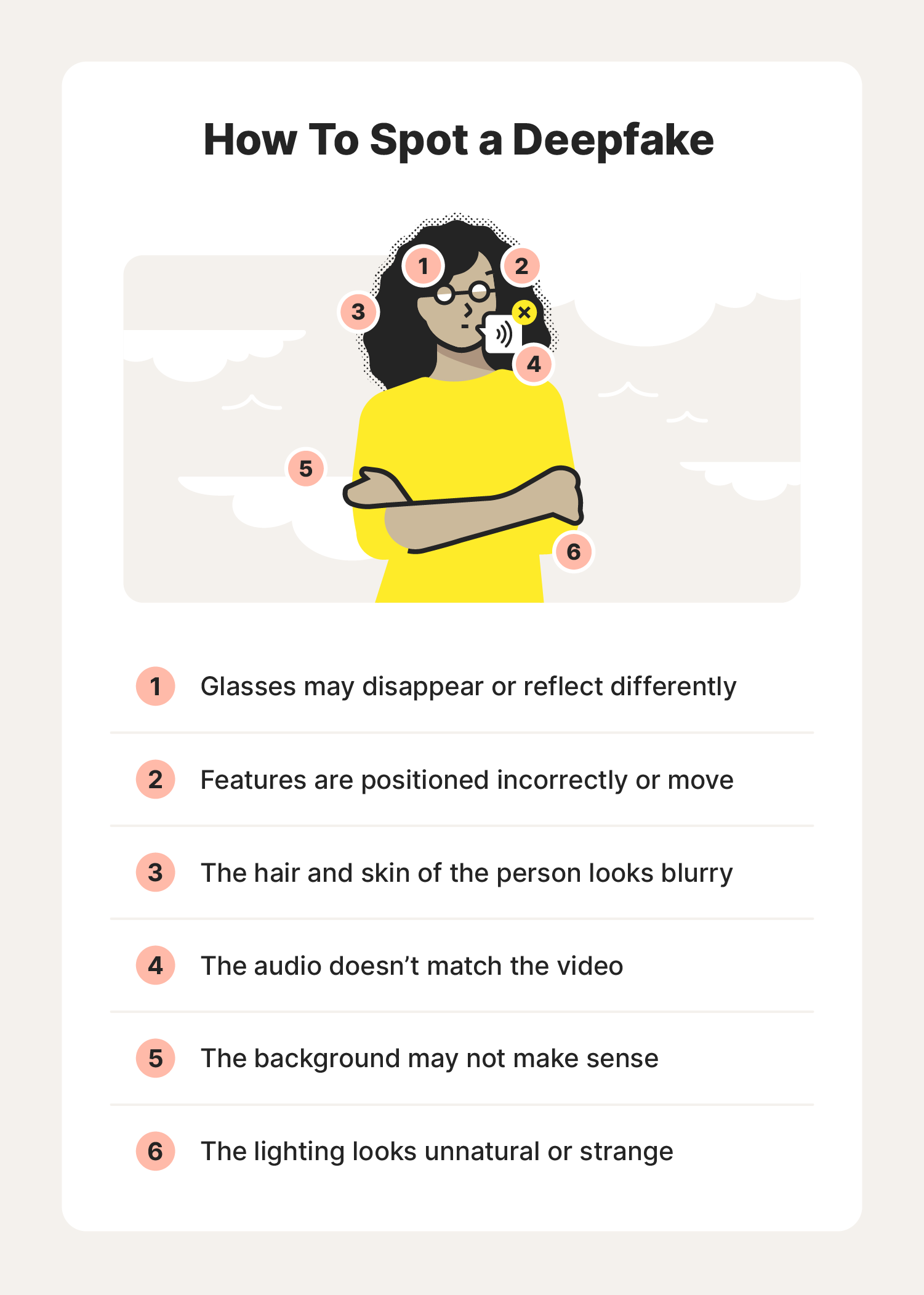

How to spot a deepfake

There are some fairly simple things you can look for when trying to spot a deepfake:

- Unnatural eye movement: Eye movements that do not look natural — or a lack of eye movement, such as an absence of blinking — are red flags. It’s challenging to replicate the act of blinking in a way that looks natural. It’s also challenging to replicate a real person’s eye movements. That’s because someone’s eyes usually follow the person they’re talking to.

- Unnatural facial expressions: When something doesn’t look right about a face, it could signal facial morphing. This occurs when a simple stitch of one image has been done over another.

- Awkward facial-feature positioning: If someone’s face is pointing one way and their nose is pointing another, you should be sceptical about the video’s authenticity.

- A lack of emotion: You also can spot facial morphing or image stitches if someone’s face doesn’t seem to exhibit the emotion that should go along with what they’re supposedly saying.

- Awkward-looking body or posture: Another sign is if a person’s body shape doesn’t look natural or there is awkward or inconsistent positioning of the head and body. This may be one of the easier inconsistencies to spot because deepfake technology usually focuses on facial features rather than the whole body.

- Unnatural body movement: If someone looks distorted or off when they turn to the side or move their head, or their movements are jerky and disjointed from one frame to the next, you should suspect the video is fake.

- Unnatural colouring: Abnormal skin tone, discolouration, weird lighting, and misplaced shadows are all signs that what you’re seeing is likely fake.

- Hair that doesn’t look real: You won’t see frizzy or flyaway hair, because fake images won’t be able to generate these individual characteristics.

- Teeth that don’t look real: Algorithms may not be able to generate individual teeth, so an absence of outlines of individual teeth could be a clue.

- Blurring or misalignment: If the edges of images are blurry or visuals are misaligned — for example, where someone’s face and neck meet their body — you’ll know something is amiss.

- Inconsistent audio and noise: Deepfake creators usually spend more time on the video images rather than the audio. The result can be poor lip-syncing, robotic-sounding voices, strange word pronunciations, digital background noise, or even the absence of audio.

- Images that look unnatural when slowed down: If you watch a video on a screen that’s larger than your smartphone or have video-editing software that can slow down a video’s playback, you can zoom in and examine images more closely. Zooming in on lips, for example, will help you see if they’re really talking or if it’s bad lip-syncing.

- Hashtag discrepancies: There’s a cryptographic algorithm that helps video creators show that their videos are authentic. The algorithm is used to insert hashtags at certain places throughout a video. If the hashtags change, then you should suspect the video has been manipulated.

- Digital fingerprints: Blockchain technology can also create a digital fingerprint for videos. While not foolproof, this blockchain-based verification can help establish a video’s authenticity. Here’s how it works. When a video is created, the content is registered to a ledger that can’t be changed. This technology can help prove the authenticity of a video.

- Reverse image searches: A search for an original image, or a reverse image search with the help of a computer, can unearth similar videos online to help determine if an image, audio, or video has been altered in any way. While reverse video search technology is not publicly available yet, investing in a tool like this could be helpful.

- Video is not being reported on by trustworthy news sources: If what the person in a video is saying or doing is shocking or important, the news media will be reporting on it. If you search for information on the video and no trustworthy sources are talking about it, it could mean the video is a deepfake.

As the technology of deepfaking advances, so will the difficulty of identifying them. That hasn’t stopped groups of scientists and programmers from creating new means of identifying deepfakes, though. The Deepfake Detection Challenge (DFDC) is incentivising solutions for deepfake detection by fostering innovation through collaboration. The DFDC is sharing a dataset of 124,000 videos that feature eight algorithms for facial modification.

There are several AI-based detection tools built to spot deepfakes, including:

Social media platforms X and Facebook have banned the use of malicious deepfakes and Google is working on text-to-speech conversion tools to verify speakers.

With all of these resources being devoted to fighting against deepfakes, combating scams is getting easier and faster with AI-powered scam detection solutions like those included in Norton 360 Advanced, which uses cutting-edge AI to detect video manipulation and fraudulent intent, for fast, reliable protection against deepfakes and other online scam techniques.

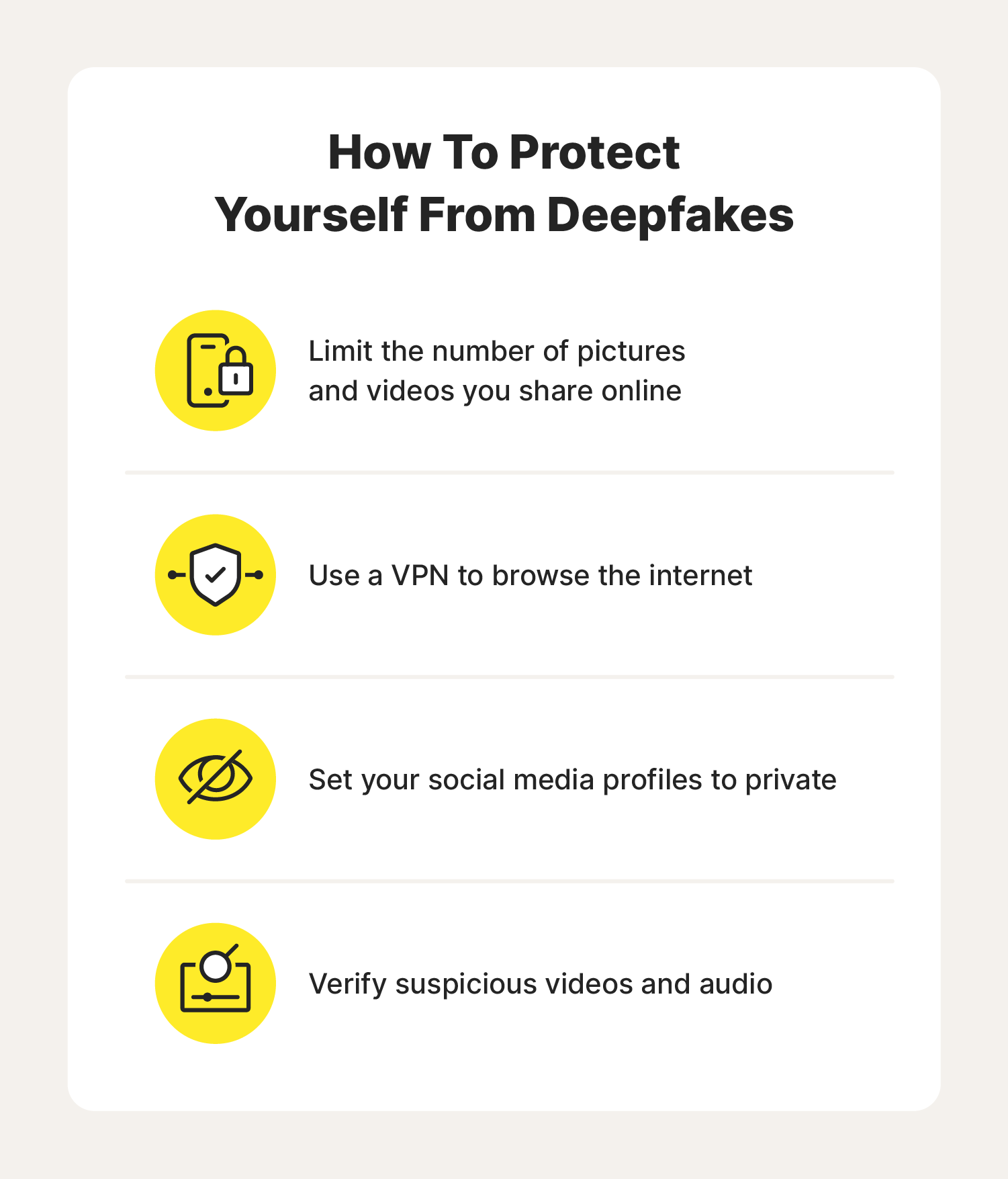

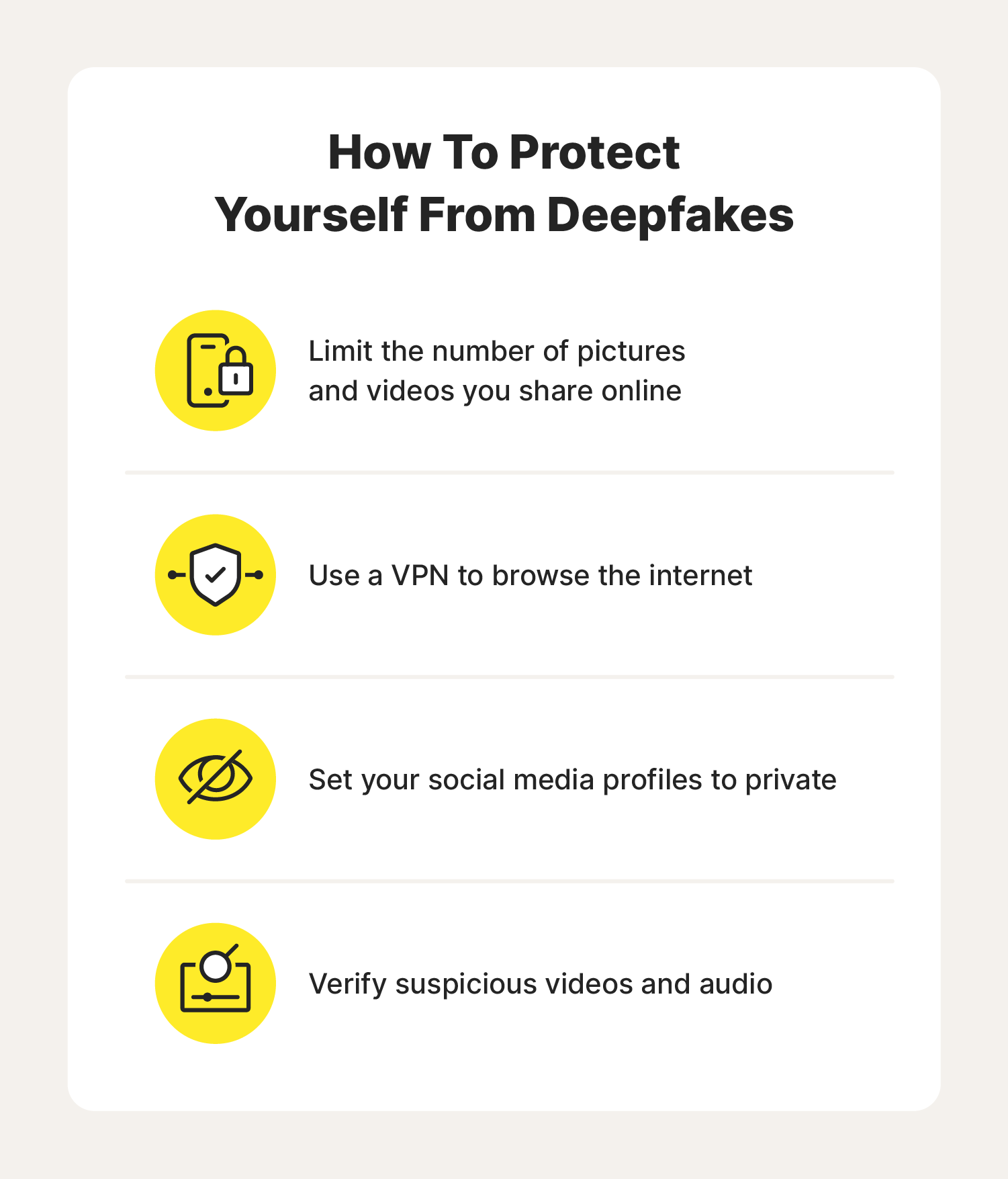

How do you protect yourself from deepfakes?

Protecting yourself from deepfakes is similar to protecting yourself from other possible threats online. To help prevent others from using your likeness in a deepfake:

- Limit how many pictures and videos of yourself and your loved ones you share.

- Make your social networking profiles private.

- Use a VPN when you use the internet.

- Use virus-blocking software.

- Have family members use a code word to identify themselves during emergencies.

- Conduct your business in person, especially if money is changing hands.

While there’s no way to completely eliminate the chances of falling victim to a deepfake scam, paying close attention to what you put out there can make a difference.

Help keep your identity safe from deepfakes

Staying cautious while browsing, shopping, or socialising online is key to avoiding deepfakes and the scams they enable. For stronger protection, sign up for Norton 360 Advanced. It features advanced AI-powered deepfake and scam detection that can alert you to threats in real time — plus you’ll receive identity restoration support to guide you through the steps to take, should you fall victim to identity theft.

FAQs

Can deepfakes be detected?

Yes, deepfakes can be detected, though it’s not always easy. You may be able to identify a deepfake with the naked eye by staying attuned to odd facial expressions, mismatched shadows, or strange audio-visual sync issues. And AI-powered detection tools can help identify tell-tale inconsistencies, deepfake “fingerprints,” and other signs of manipulation.

Is a deepfake identity theft?

A deepfake in and of itself isn’t identity theft, but it can be used as part of a phishing scam or impersonation scheme that leads to identity theft, by tricking someone into sharing private information.

Are deepfakes really a security threat?

Potentially, yes. As deepfake technology becomes more advanced and accessible, it can be used to spread disinformation, impersonate public figures, disrupt elections, or conduct scams, making it a growing security concern.

Who is affected by deepfakes?

Nearly anyone can be affected by deepfakes. You might encounter a fake video and believe it’s real, or worse, someone might create a deepfake of you and share it without your consent. From public figures to private individuals, deepfakes pose risks to reputation, privacy, and trust.

Editorial note: Our articles provide educational information for you. Our offerings may not cover or protect against every type of crime, fraud, or threat we write about. Our goal is to increase awareness about Cyber Safety. Please review complete Terms during enrollment or setup. Remember that no one can prevent all identity theft or cybercrime, and that LifeLock does not monitor all transactions at all businesses. The Norton and LifeLock brands are part of Gen Digital Inc.

Want more?

Follow us for all the latest news, tips, and updates.